I wrote this article for Pierre AJ Sabourin, and although it’s about art history more than anything else, it’s also a good travel and outdoor adventure piece. It truly is a great guide to discovering Canadian wilderness through Group of Seven art. Writing it inspired me to try some art-oriented hikes this summer, so keep an eye out for follow-up posts!

To follow in the footsteps of the Group of Seven takes an adventurous spirit and sturdy shoes. To see the actual locations of Group of Seven paintings, fans of the Canadian art movement must leave the city’s cozy galleries, traipse to the end of all roads, and lose themselves in Ontario’s backcountry wilderness. Not everyone is up for it, for visiting a painting site is not a simple matter of reading a title — the members of the Group of Seven did not always name their pieces according to location. They were often composites of multiple locations or the painters tried to improve their sales by identifying renowned areas.

But, a few individuals have made serious headway in identifying the favourite haunts of the iconic Group of Seven. Pierre AJ Sabourin, En Plein Air Landscape Artist, devotes his career to painting his own interpretations of Group of Seven sites and imparting his passion to his students. Jim and Sue Waddington have made a decades-long quest out of ascertaining the precise whereabouts of over two hundred paintings. And others have joined them in the pursuit for demystifying this important legacy.

Perhaps three years ago, Pierre AJ Sabourin was introduced to Jim and Sue Waddington by friend and La Cloche photographer Jon Butler and his wife Kerry, who live in Willisville. The Waddingtons had been researching the area and, curious to speak to Pierre about his discoveries, they spent an afternoon with him at his home in Killarney.

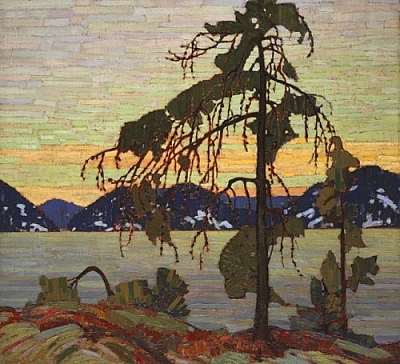

Sabourin is based at Sunset Rock Studio, which he chose specifically because he suspects it to be the true site providing the inspiration for Tom Thomson’s The Jack Pine. Pierre maintains that Rat Portage, the gateway to Frazer Bay, is an identifying feature of the painting. He points out that the colour of the water is more reminiscent of Killarney than Algonquin (where it is generally thought the piece was created), and standing on the rock provides a westerly view, crucial for a sunset painting. Moreover, while many believe the white in the piece to be snow, Pierre reasons The Jack Pine is in reality set against the white quartzite rocks of Killarney, which were deforested at the time. As Pierre recalls, the Waddingtons agreed with him that the location attributed to the painting in Algonquin Park doesn’t resemble the picture, and told him the idea was plausible.

But for Pierre, the real proof lies in his family’s history. Sunset Rock Studio has always belonged to Pierre’s relatives. It was built by Charlie Lowe, Pierre’s great-uncle. At the time, Charlie worked with his father for the family’s fishing business. Sunset Rock Studio served as a support cottage for the business. The family would spend their summers in Killarney, but come autumn, they would take their fishing boat, the AJ Lowe, to Owen Sound, where they spent their winters. Charlie and his father at different times and on repeat occasions brought various members of the Group of Seven, including Tom Thomson and his brother George, from Owen Sound to Killarney, where Sunset Rock Studio was their guesthouse. Charlie’s father had two of George Thomson’s paintings in his home, but they were sold when he passed away. Knowing how much time the Group of Seven and especially Tom Thomson spent at Sunset Rock Studio, Pierre is convinced that he’s right about The Jack Pine.

Sabourin has furthermore deduced that FH Varley’s Stormy Weather, Georgian Bay was really painted from the Fox Islands, off the coast of Killarney on the Georgian Bay, though traditional accounts place the site in a more southerly part of the bay (the island in question belonged to a friend of the Group of Seven, one Dr. MacCallum). Again, family history comes into play as the Lowes had camps on the Fox Islands, which they used on extended fishing trips. They often brought members of the Group of Seven here. “When you look at the painting,” Pierre says, “Varley paints very stormy clouds. He doesn’t show the mountains, but look closely and you’ll see the outline of mountains with cloud cover. The shapes of the mountains on the horizon match up perfectly.” To demonstrate his idea, Sabourin painted Georgian Bay from the same spot.

While no doubt others have painted from this next corner of George Lake before him, Sabourin thinks he’s the first to make a connection between the site where he painted Killarney Provincial Park and Franklin Carmichael’s La Cloche Landscape. Standing on a point in late Fall, absorbed in his work, Pierre was already spooked by the atmosphere when a beaver slapped its tail in the water behind him, the echo resounding loudly in the mountains. Startled — scared — Pierre’s palette, easel, and painting were knocked into the water. Pierre laughs as he admits he got caught by a beaver and had to start his painting all over again.

Less controversial for Pierre is the site of JEH MacDonald’s Thomson’s Rapids, Magnetawan River, which Pierre rendered while on an expedition with his students.

On the other hand, Pierre believes that the place from which he interpreted Hope Whispered (Knoefli Falls) was also the true location of MacDonald’s Batchewana Rapid, which is usually attributed to somewhere in Algoma on Lake Superior.

The Waddingtons have made many of their own fascinating discoveries. Their journey began some thirty years ago when they encountered the site of Hills, Killarney, Ontario (Nellie Lake) by AY Jackson, and unwittingly photographed many more, which they were able to identify a few years later. One of their biggest achievements was uncovering the rock on which Franklin Carmichael sat painting while photographed by fellow artist Joaquim Gauthier. They made several trips there, only to eventually find the rock had disappeared. Together with the help of Jon and Kerry Butler and several other volunteers, they traced the rock to the bottom of the hill and returned it to its rightful position.

The Waddingtons put together an exhibit of their findings at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in 2010, which was accompanied by an excellent interactive website providing videos, photos, audio clips, and textual explanations of their adventures, along with background on the Group of Seven and their role and influence on the Canadian and international art scenes, provided by the gallery. The website includes educational resources and lesson plans for educators as well as a forum for independent explorers to post their own photos. The Waddingtons have since toured across the country to speak about what they have learned.

Quickly gaining renown amongst Group of Seven enthusiasts, travel bugs and canoeists have sought them out for advice and guidance. One such admirer was Julian Beecroft, an Irishman with Canadian roots who travelled for seven weeks across the country, blogging about his own finds along the way. Coast to Coast with Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven complemented a Group of Seven exhibit at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in England. He describes his own experience at the traditional site of Varley’s Stormy Weather, Georgian Bay in his Southern Ontario: Toronto and Georgian Bay post. Interestingly, Beecroft and Sabourin both observe — though the former from the usual view on Dr. MacCallum’s island and the latter from Sabourin’s suggested Fox Islands — that water levels were higher then and more shoals are visible now.

Similarly, Preston Ciere of Portageur.ca has had his own escapades finding Carmichael’s Rock Overnight with his wife and canine companions. Trees that have grown since the park formed, after Carmichael had painted the scene, made the feat more difficult, but rewarding.

Changes to the landscape have bewildered some of the others, too. But often times, the artist’s interpretation rather than re-creation of nature could be just as confusing. And sometimes, the members of the Group of Seven downright lied about the locations of their paintings. Unable to sell their works though their exhibits drew massive crowds, Group of Seven members were not above telling potential buyers what they wanted to hear. Pierre AJ Sabourin claims, “15,000 people would come to a show, and they never sold anything.” Pierre quotes AY Jackson, who told a potential buyer, “I have every painting I have ever done in my life in my home.” To demonstrate, Sabourin tells of an AY Jackson painting with a note at the back indicating a site in Quebec, but the Waddingtons have proved it to be in Killarney. “It’s the same with identifying Algonquin,” says Pierre. “People in Toronto knew it; they didn’t know Killarney.”

To confound Group of Seven researchers even more, members would create composite images — in every way their right as artistic creators, but puzzling for site-seekers nonetheless. The Waddingtons reveal the steps they take to overcome these challenges in their discussion of Arthur Lismer’s Bright Land, a painting impossible to find until an earlier version with a clue in its title led them to discover where the masterpiece, indeed a composite, had been envisioned. Astonishingly, Sabourin had realized that Bright Land had been painted on Topaz Lake fifteen years ago, when he himself was painting there. Still, the investigative work done by the Waddingtons has aided others like Julian Beecroft in achieving success. Beecroft was able, with the Waddingtons’ help, to visit and confirm the site of Franklin Carmichael’s Grace Lake, which the Waddingtons had researched and actually placed on Frood Lake. Beecroft likewise noted the addition of features from the commonly accepted view on Grace Lake, as well as changes to the natural landscape.

Following in the footsteps of the Group of Seven has become an intriguing pastime for outdoors enthusiasts, art lovers, history buffs, culture seekers, and travellers. As Preston Ciere says, it’s all about the location. It just might not look like anything you expected.

Disclaimer

Group of Seven images on this page are believed to be in the public domain. Other images have been reproduced with permission.

This article is cross-posted from Discovering the Canadian Wilderness Through Art: Following in the Group of Seven’s Footsteps via Pierre AJ Sabourin.

Search Niackery

×